Everything In Its Right Place: Pt3

Everything In Its Right Place: Pt 3

In the previous article in this series we added bins, or free lists, to our implementation and demonstrated how we could leverage a use-after-free vulnerability to corrupt the header data of a freed chunk located in the fast bin and gain the ability to overwrite arbitrary memory addresses.

In this article, we will be introducing the concept of arenas, showing how we can add arenas to our implementation, and demonstrate a ‘house of force’ style attack to hijack execution.

What is an arena?

An arena is essentially a structure that is used to store the state of a program’s heap. It stores items such as the bins associated with the heap, pointers to other arenas, as well as a pointer to the ‘top’ of the heap. Most memory allocators allow for multiple arenas to prevent heap contention for multi-threaded applications, but for simplicity we will only be implementing a single main arena.

Let’s take a look at our basic arena structure.

struct mmalloc_state {

binptr sortedbins;

binptr fastbins[NFASTBINS]; chunkptr top; struct mmalloc_state *next;

};

Here we can see that we have moved our sorted bin and fast bin pointers into the structure, we also introduced two new fields; top and next. We can disregard the next pointer for now, since we will only be creating a single arena, this field will not be used. The top field is used to point to the last chunk in the heap, this chunk will always remain unallocated and is used as a large bank of memory that we can split to create new chunks.

Top Chunk

To properly use the top chunk, we must adjust our allocation strategy. In the previous implementations, any time an allocation request could not be served by an existing freed chunk, we would make a call to sbrk() to extend the size of the heap with enough space to satisfy the allocation request. This strategy is inefficient as it increases the amount of time switching between user space and kernel space. Our new strategy will involve requesting a large default allocation when the heap is initialized and setting that allocation as the top chunk. Then any following allocations which are not served by bins will be split from the top chunk, and the size and position of the top chunk will be adjusted accordingly. Using this strategy, the only time we should have to call sbrk() to extend the heap will be when the top chunk has run out of space to serve new allocations.

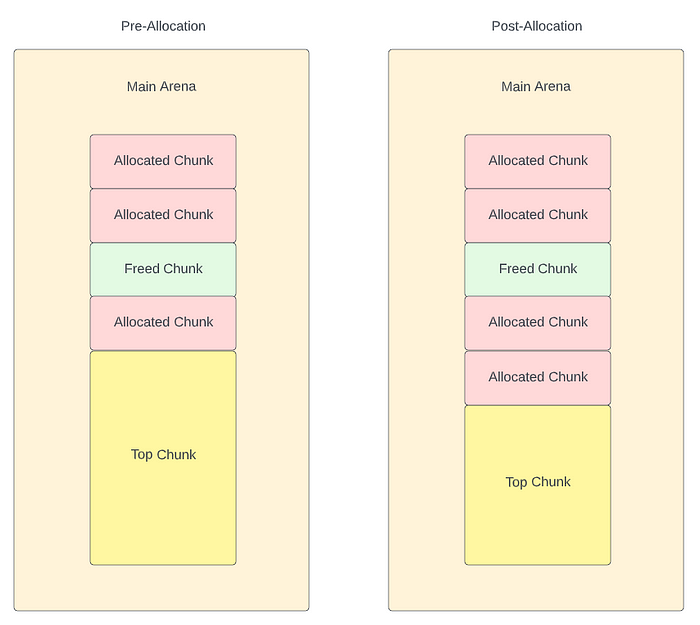

Considering these adjustments, we can visualize an allocation from the top chunk as follows.

As we can see, the newly allocated chunk is split from the beginning of the top chunk, which places it directly after the previously allocated chunk. As a result of this split, the top chunk shrinks in size.

Top Chunk in mmalloc()

To apply this new allocation strategy, three functions were created to interact with the top chunk; create_topchunk(), split_topchunk(), and extend_heap(). Each of these functions is called by the req_space() function that we had previously used as a function to extend our heap using sbrk(). The new req_space() now acts as a wrapper for these new functions and is defined as follows.

struct chunk_data *req_space(size_t size) {

struct chunk_data *chunk = NULL;

if(!main_arena->top) {

main_arena->top = create_topchunk(TOP_SZ);

}

if(main_arena->top->size > (size + CHUNK_SZ)) {

chunk = split_topchunk(size);

} else {

extend_heap(size);

chunk = split_topchunk(size);

} return chunk;

}

If the first condition evaluates as NULL, this indicates that the top chunk in the main arena has not been created and create_topchunk() is called.

struct chunk_data *create_topchunk(size_t size) {

struct chunk_data *top;

top = sbrk(0); void *req = sbrk(size);

assert((void *)top == req);

if(req == (void *)-1) {

return NULL;

}

top->size = (size - ALLOC_SZ);

top->fd = NULL; return top;

}

The create_topchunk() function makes the initial call to sbrk() with the default top size, which in our case is defined as such

#define TOP_SZ 32000

Once this call is made, the size field of the top chunk is set to the new size minus the size required for an allocated chunk header, the fd field is set to NULL, and the top chunk is returned.

The second condition in req_space() compares the size of the top chunk to the size of the allocation request plus the size of the chunk header. If the top chunk size is greater, this indicates that there is enough space to carve out a new allocation from the top chunk and split_topchunk() is called.

struct chunk_data *split_topchunk(size_t size) {

struct chunk_data *chunk;

size_t top_sz = main_arena->top->size;

chunk = main_arena->top;

chunk->size = size;

main_arena->top = (void *)chunk + (size + ALLOC_SZ);

main_arena->top->size = top_sz - (size + ALLOC_SZ);

main_arena->top->fd = NULL; return chunk;

}

Here we can see that a new chunk pointer is created and set to the top chunk pointer. The top chunk pointer is then increased by the size of the allocation and the top chunk size field is decreased by the same size which effectively shrinks the top chunk. The newly created chunk is then returned.

The final condition in req_space() indicates that the top chunk has been initialized but it does not have enough space to satisfy the allocation request. If this condition is met, extend_heap() is called.

int extend_heap(size_t size) {

void *top = sbrk(0);

void *req = sbrk((size + ALLOC_SZ));

assert(top == req);

if(req == (void *)-1) {

return -1;

} main_arena->top->size += (size + ALLOC_SZ); return 0;

}

extend_heap() functions similarly to how req_space() did in our previous implementation by making calls to sbrk() to extend the heap. Once the heap has been extended, req_space() makes another call to split_chunk() to make use of this newly added heap space.

Allocation in Action

Let’s take a look at what the heap look like in a debugger after making these changes in our implementation. First we will create a sample program that creates two chunks and uses memset() to set the useable area of the chunk to easily identifiable values.

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

void *test, *test2; test = mmalloc(32);

memset(test, 0x41, 32);

test2 = mmalloc(32);

memset(test2, 0x42, 32);

return 0;

}

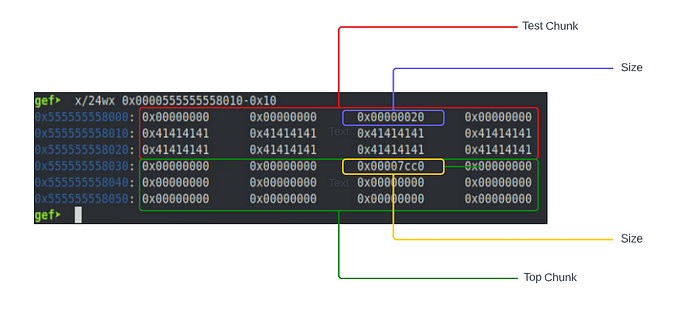

Next we will load this sample program with GDB and set a breakpoint after each call to memset(). After our first breakpoint, the heap looks as follows.

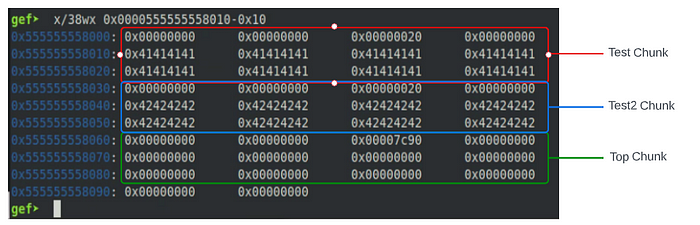

We can see from the image above that our chunk allocated for the test variable is located directly above our top chunk. If we continue running this sample program in GDB then inspect the heap, we can see how the chunk allocated for the test2 variable will be located directly after the chunk allocated for test, and the top chunk position and size will change accordingly.

House of Force(ish) Attack

Now that we understand how our top chunk is initialized and used, let’s take a look at how we can exploit an inherent flaw in it’s design. The ‘House of Force’ attack was described in the famous ‘Malloc Maleficarum’ article: https://dl.packetstormsecurity.net/papers/attack/MallocMaleficarum.txt and is essentially a technique where by corrupting the size value of the top chunk, an attacker can allocate a chunk that is located outside of heap space and overwrite an arbitrary memory location. While the GLIBC implementation of malloc() behaves a bit differently and has some size validations, our implementation is much more simple and makes this attack easier to achieve.

Based on the description of how the top chunk functions and how new chunks are allocated from it, we know that the most recent allocation should be located directly in front of the top chunk. This means that if we are able to perform a heap overflow on the most recently allocated chunk, we can overflow into the top chunk and corrupt the header. By corrupting the size field of the top chunk, we can trick the allocator into thinking that the heap is much larger than it actually is. If we are then able to control two additional allocations, we can get mmalloc() to return a area of memory outside the heap that we can control.

Target

For the previous articles in this series, all allocator and sample code was self contained in one program. Based on the nature of this attack and the target that was chosen to overwrite, I decided to compile the mmalloc() code as a shared library and create a sample that used this library. The main reason for this is the target address we are going to overwrite will be an entry in the GOT (global offset table), and the use of the shared library provided more entries (and necessary padding we will discuss later) to target.

To demonstrate this attack, let’s expand our sample from earlier to include an additional mmalloc() call, then let’s overwrite past the boundaries of the associated chunk to simulate a heap overflow.

test = mmalloc(32);

memset(test, 0x41, 32);test2 = mmalloc(32);

memset(test2, 0x42, 32);test3 = mmalloc(32);

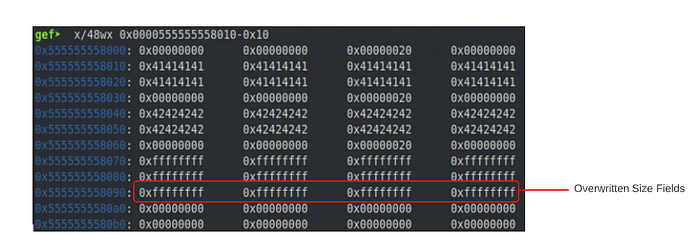

memset(test3, 0xFF, 48); //overwrite 16 bytes past the end of test3

If we take a look at the heap at this point, we can see the three allocated chunks, as well as the top chunk with an overwritten prev_size and size field.

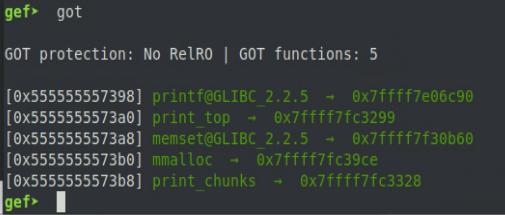

Now that we have changed the size of the top chunk to equal 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF (-1 signed or 18446744073709551615 unsigned) we need to find an entry in the GOT table that we want to overwrite and calculate the offset between that entry and the top chunk. Taking a look at the GOT in GDB we can see what our options are.

For our particular use case, the entry for memset() is our best option for a target. We can’t overwrite mmalloc() as we need to make another allocation after we overwrite the GOT entry to complete this attack. We also can’t overwrite print_chunks() or print_top() in this case due to the behavior of mmalloc() and split_topchunk().

This is because split_topchunk() will set the size field of the newly allocated chunk during its operation, and mmalloc() will return a pointer to 16 bytes after the start of the chunk to compensate for the header fields. Looking back at the GOT, we can see that each entry is only 8 bytes apart from each other. This means that when split_topchunk() is setting the size field of the chunk that we are allocating it is actually overwriting the previous entry in the GOT. So for example, if we attempt to overwrite the entry for print_chunks() we end up overwriting the entry for mmalloc() and if we attempt to overwrite print_top() we end up overwriting the entry for printf() (which print_top() relies on).

To properly overwrite one of these entries, we need to allocate a chunk that spans the size between the top chunk and the target minus 32 bytes to compensate for the extra space allocated for the chunk headers. Then we need to allocate another chunk of an arbitrary size (as long as it is less than the remainder of the top chunk’s size) which will return the address of the GOT entry which we will overwrite. Looking at the address of the top chunk and the address of the GOT entry for memset(), we can easily calculate the necessary size to allocate.

(0x5555555573A8 - 0x555555558090) - 32 = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFF2F8

Let’s add another call to mmalloc() with this size, then an additional call to mmalloc() which will return the address we wish to overwrite.

test4 = mmalloc(0xFFFFFFFFFFFFF2F8);

functest = mmalloc(64);

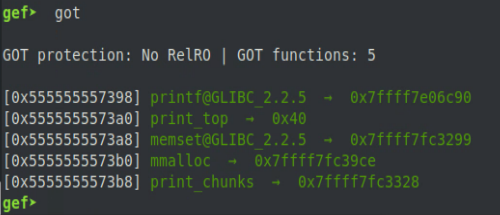

If we take a look at the GOT after these calls to mmalloc() we can see how the entry prior to memset() in the GOT gets overwritten as mentioned earlier.

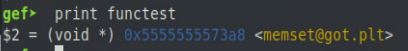

Also, if we take a look at the address of our functest variable, we can see that it is pointing to the address of memset() in the GOT.

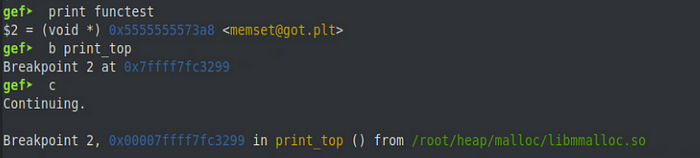

Now we can write an address to this location and execute memset() to redirect the execution to a function of our choosing. In this case, we will write the address for the print_top() location which as seen in our previous view of the GOT (prior to it being overwritten at least) is equal to 0x7ffff7fc3299.

strcpy(functest, "\x99\x32\xfc\xf7\xff\x7f");

memset(functest, 0x41, 1);

Now when the call to memset() is executed, it will instead execute the print_top() function. We can confirm this by setting another breakpoint for print_top() and continuing execution in GDB.

Wrap up

In this article we explored the concept of Arenas and the top chunk, and demonstrated how we could use a heap overflow to corrupt the top chunk size and overwrite an entry in the global offset table to hijack execution. Writing these articles has been really helpful to my own understanding of memory management and associated vulnerabilities, and I hope that others have found them useful as well!